What Makes LLMs So Fragile (and Brilliant)?

They can feel like geniuses one moment & confused muppets the next. But within their internal geometry it's token-by-token “arbitration” that makes them both startlingly robust and strangely brittle.

In my last post I painted a picture where you imagine you’re chatting with an LLM about quantum mechanics. You ask it to explain Bohr’s model of the atom and compare it to Schrödinger’s.

Let’s revisit that starting point, but this time we’ll explore 2 different paths it might follow. Perhaps it gives you a clean, historically grounded answer. Then you tweak the prompt slightly (change a clause or add an extra request) and suddenly it fumbles something basic, or hallucinates a citation that doesn’t exist.

How does this really work in detail? It’s the same weights. The same training. Almost the same words in…yet wildly different quality out.

From the outside, it’s tempting to shrug and say “meh, it’s just probabilities” or “sometimes the world model fires, sometimes it doesn’t”. But that doesn’t really explain why tiny changes produce such different behaviours in the first place.

In recent posts we’ve explored a useful picture:

The 3‑process view: models are always juggling compact internal states, recomputed routes, and early anchors.

A sharper definition of a latent model: not just any feature, but a portable internal scaffold that represents, predicts, and responds to interventions.

And then the obvious question: does having a latent model equal understanding? (Short answer: not by itself, but it gets us close to where understanding would live, if it shows up.)

This post looks over the next ridge of that same landscape. Now we’ll ask a more local question:

What makes LLMs so fragile (and so brilliant) if the latent machinery is the same in both cases?

To answer that, we need to zoom in to a single decoding step and look at something I’ve been calling arbitration: the quiet process by which the model decides, token by token, how much to trust its own states, its habitual routes, and its anchors.

The short version is:

The brilliance comes from how fluidly the model can re‑weight those three processes on the fly.

The fragility comes from the fact that this arbitration policy is itself a messy, learned object shaped by geometric negotiation.

You don’t need to know any linear algebra to follow the story, but it will help to have a mental picture of a point moving through a landscape.

One step in from the edge: a single token in motion

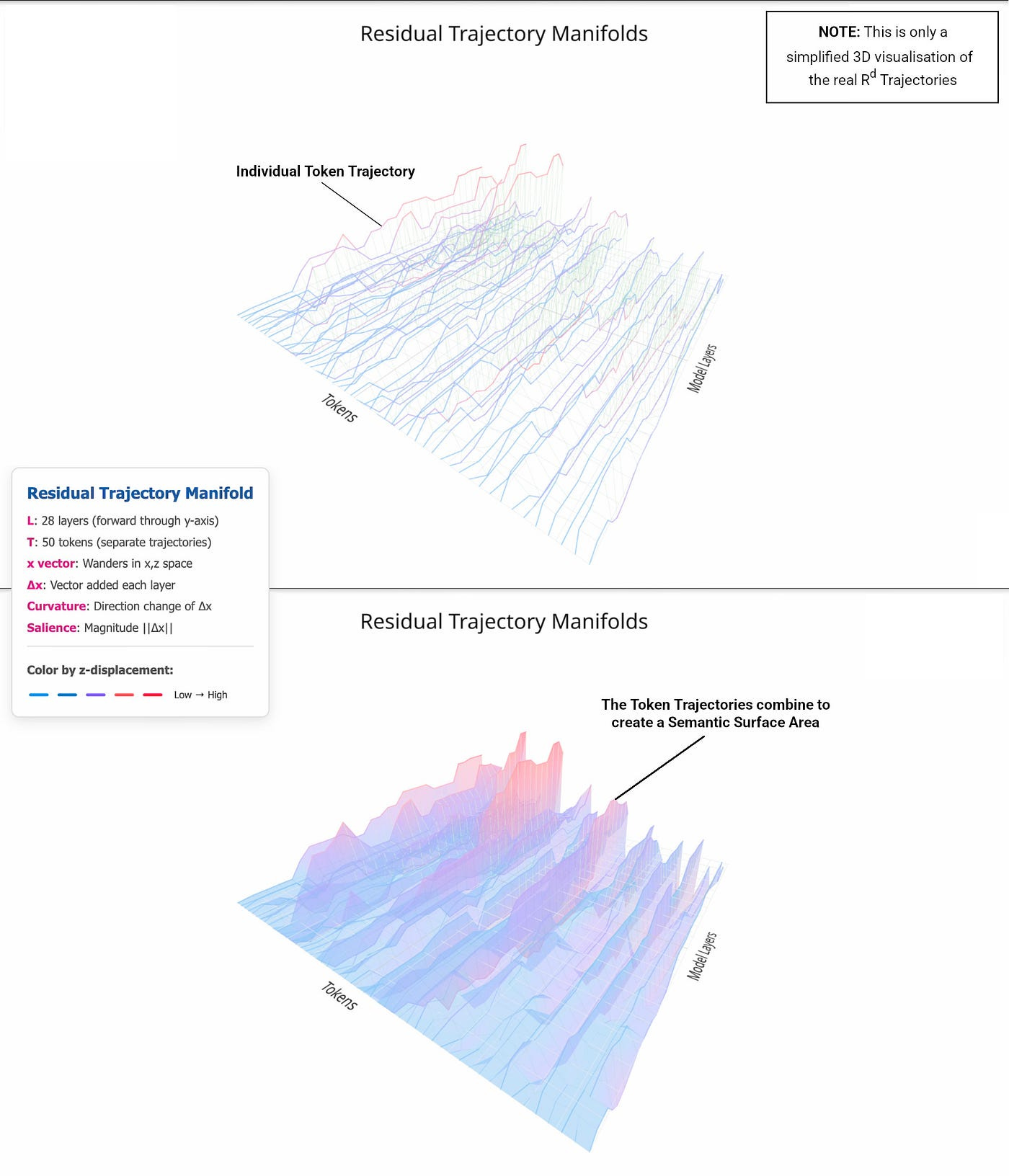

When an LLM generates the next token, it doesn’t pull a word out of a hat. Inside the network, there’s a high‑dimensional vector called the residual stream - a kind of running scratchpad the model updates at each layer.

You can imagine that scratchpad as a point in a huge space. At every layer, a few things happen:

Attention heads look back over the previous tokens, decide which ones to care about, and add in information from them.

MLPs (little feed‑forward networks) push the point in directions that capture familiar patterns and features.

Layer by layer, these forces accumulate. By the time you reach the bottom of the stack, the final position of that point determines which token is most likely.

Now overlay the 3‑process view on that picture:

States are particular directions or subspaces in this space. When the model writes a state like “we’re in formal‑proof mode” or “this story is about Alice”, it’s driving the residual point into a recognisable region.

Routes are familiar paths through the space. If the last few tokens look like the start of a proverb or a for‑loop, the MLPs and short‑range heads know which way to head next.

Anchors are strong, early influences - the system prompt, the first instruction, the initial examples. Attention keeps pulling from those positions and re‑injecting their features.

On each token, all three are in play. The question isn’t “does the model have states?” or “does it use routes?” It’s:

Right now, which of these forces actually moves the point in the direction that decides the next token?

That’s what I mean by arbitration.

Arbitration is not a separate module. There’s no little controller branching “if X then trust state”. Instead, it’s an emergent property of how attention heads and MLPs are wired, how they interact and how strongly different features couple to different tokens.

To see why that matters, it’s useful to anthropomorphise the attention heads just a little.

The many moods of attention heads

Under the hood, an attention head does something very simple: it takes the current residual stream scratchpad, treats it as a query, compares it to a set of keys built from previous tokens, and uses that to mix together their values.

That’s just matrix multiplication.

But with training, different attention heads specialise. When you look at them through the lens of states, routes and anchors, you start to see familiar characters.

There are heads that mostly stare at the previous few tokens - local pattern heads. They’re the route followers: great at closing brackets, continuing idioms, filling in “Once upon a … time”.

There are heads that reach far back into the context - long‑range heads. Some of these behave like state readers: they keep track of which variable is which, who said what, what the current problem is.

There are anchor heads that keep glancing at the system prompt or the first user message. They carry safety instructions, style, and high‑level constraints forward.

There are bridge heads that link distant regions of text: they see that a name introduced early is the same entity appearing much later, or that a question and an answer section belong together.

On any real token, several of these are active at once. Each head pulls information from its favourite tokens and adds its own update to the residual scratchpad. The MLPs add their pushes too.

If you freeze time and look at that residual stream scratchpad (their activations), you’ll see it has the sum of many such updates:

some pulling it towards “continue the pattern”

some pulling it towards “respect this plan or fact”

some pulling it towards “stay in this style and don’t cross these lines”

The final outcome of that tug‑of‑war is the token you see.

This is the arbitration:

the balance of influence between pattern‑followers, state‑readers, and anchor‑keepers on this particular step.

When people talk about an LLM “ignoring instructions” or “going off the rails”, what they’re usually noticing is a change in that balance.

When arbitration lines up - why they feel brilliant

Start with a case where the LLM looks smart.

You give it a clear question, in a domain it’s strong in. You say “work step by step”. Maybe you add a hint about the style you want. The answer you get is structured, accurate, and on‑tone.

Internally, a few things have gone right:

Early in the context, some heads write a state like “we’re solving a maths problem” or “we’re writing Python”. That state becomes part of the residual and stays there.

Other heads treat that state as important. When they decide where to look next, they give more weight to tokens that carry the plan or the key facts.

The “think step by step” cue flips some heads into a regime where they spend more of their budget reading and updating states, and less simply following local patterns.

Anchor heads keep re‑injecting the global constraints like “stay in the requested language”, “follow the safety rules” or “maintain the requested tone”.

The routes are still there (the model is still using its habits for syntax, punctuation and stock phrases) but they’re operating inside a frame that’s being actively maintained by state and anchor‑sensitive heads.

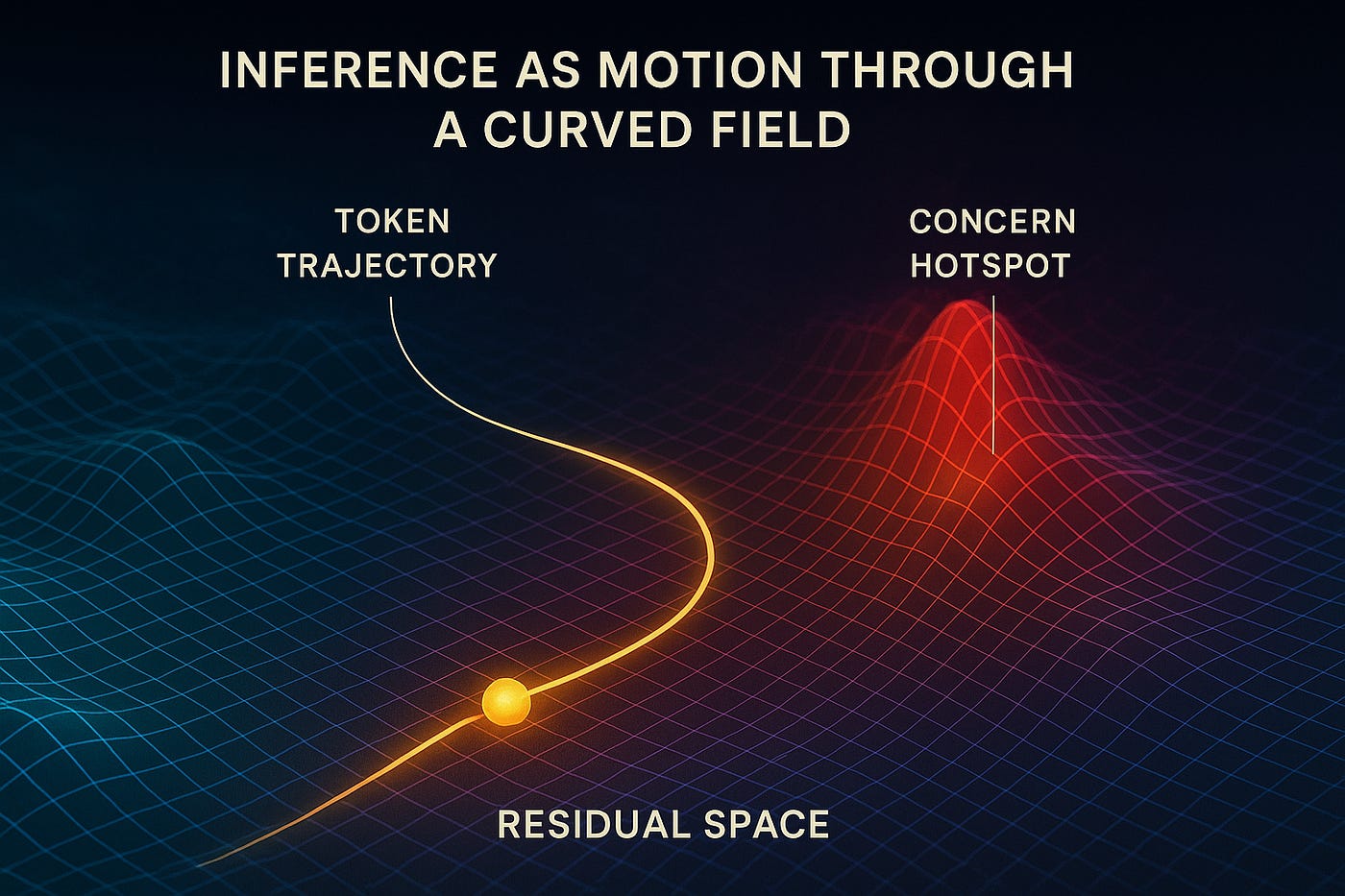

In Curved Inference terms, the trajectory of the residual point bends into a basin shaped by that state, then flows along it. Small paraphrases of the question don’t knock it out of that basin. The internal geometry is doing some work to stabilise the path.

From the outside, that’s what “robust competence” feels like. Inside, it’s arbitration that has given the “right kinds of heads” more pull.

When arbitration wobbles - why they feel fragile

Now lets explore the opposite story.

Imagine the model has just done a nice, step‑by‑step derivation and is about to state the final answer.

Everything up to this point suggests it “knows” the answer. Textually and internally, it’s written the right states.

But on that final token, the dynamic can change.

The explicit reasoning is done. The context now looks, to the model’s pattern recognisers, a lot like the endings of thousands of other maths answers it’s seen. The local cues say: “this is where people usually say ‘Therefore, the answer is …’ and then a familiar‑looking number”.

Short‑range heads and MLP routes that specialise in this pattern fire strongly. A weaker, longer‑range head that would go back and check the computed result doesn’t quite win the competition inside the residual.

The result - the model confidently outputs a plausible but incorrect result. From our point of view, it has betrayed its own reasoning. From the geometry point of view, the wrong set of influences dominated the vector sum.

That’s route‑led arbitration in a place where state‑led behaviour would have been better.

See the “Can you beat 17?” example

You see similar effects with instruction following.

Sometimes a system prompt says “be concise” and the user later says “give me all the details”. If the heads that read user instructions and the heads that stick to the original style anchor are finely balanced, small changes in wording can flip which side wins. One version of the prompt lets the “update the style” heads strengthen a new state. Another keeps them just weak enough that anchor heads dominate.

From the outside, that looks like an unpredictable change of mind. Inside, it’s a decision boundary in a hidden geometric space.

These are not edge cases. They’re baked into how the model works. The same machinery that lets it dynamically trade off between states, routes, and anchors is what makes it exquisitely sensitive to how you phrase things.

Two failures that aren’t about missing knowledge

There’s a temptation to explain every LLM mistake as “it never learned X”. Sometimes that’s true. But two very common failures are really about arbitration, not absence.

The first is latent amnesia.

The model has clearly demonstrated that it can represent some fact or structure elsewhere – maybe in the same conversation, maybe earlier in the answer. But in a particular stretch, the heads that would read that state just don’t have enough influence.

The residual stream scratchpad contains the relevant direction (“Alice is the detective”), but for a few tokens the active pattern heads are mostly looking at local n‑grams and stylistic cues. The residual is steered by routes that don’t care about who‑is‑who. The result is a small contradiction or a dropped detail.

The second is anchor lock‑in.

Here the problem isn’t that the model never updates - it’s that some early piece of context has planted a strong, durable feature that later words struggle to dislodge.

A style instruction, a safety note, the topic of the first example - all of these can produce features that many heads treat as privileged. If you later try to pivot (“now switch to a sombre tone” or “now ignore that constraint”), the new states get written but never fully win.

Both of these are arbitration problems. The relevant latent models exist in the weights and sometimes even in the current scratchpad. But the heads that could bring them to bear aren’t the ones steering the final few steps.

This is part of why LLMs can feel inconsistent or “moody” - the internal balance of power between different groups of heads can shift with subtle changes in prompt shape, length or recent tokens.

Visualising the geometry: three forces on one path

The geometric picture makes this complex interaction clearer, you can imagine each token’s computation as a short segment of a path in a high‑dimensional landscape.

Along that path, three families of forces are interacting:

State forces push the path to stay within certain corridors: “keep the argument coherent”, “honour this plan”, “remember who Alice is”. They’re like invisible walls that bump you back if you start to drift.

Route forces pull the path towards well‑worn grooves in the terrain: “after these words, that phrase usually comes next”, “this is the rhythm of a bullet list”, “this is how JSON usually continues”.

Anchor forces act like distant mountains or gravity wells: the initial instructions and early examples warp the whole landscape, so parts of it are easier to roll into than others.

Arbitration is just the relative strength of those forces at each step.

When state forces are strong and well‑aligned, the path follows a smooth curve through a stable valley. Small perturbations don’t throw it out - it bends back. That’s robustness.

When route forces dominate, the path hugs familiar grooves and can overshoot important turns. It’s fast and fluent, but brittle to shifts in the underlying problem.

When anchor forces are overwhelming, the whole path runs down one side of the mountain whether or not that’s where the current evidence points.

The same model can occupy all three regimes, depending on the prompt. What looks like “fragility” is often just the system skating right on the edge between them.

Curved Inference is about measuring these shapes directly - how paths bend, where they converge, which regions of the space get revisited when a latent model is active. Arbitration is the day‑to‑day physics that gives those curves their character.

Why is this way of looking at fragility so useful?

You can tell two stories about LLM fragility.

One is fatalistic - “they’re just stochastic parrots so of course they glitch”. That doesn’t help you design better systems, safer interactions, or more meaningful evaluations.

The other is to focus too much on the world‑model story - “they have a world model but sometimes it doesn’t fire”. That makes the model sound like a person having an off day. It also hides the actual mechanics behind a vague metaphor.

But the 3‑process view plus arbitration and geometry gives you a third option.

Now you can say: there really are internal scaffolds (latent models) that behave like small, usable programs inside the network. But at every step the LLM machinery has to decide, implicitly, how much to let those scaffolds steer versus its local habits and its early commitments. That choice isn’t a free‑floating “will” - it’s shaped by which heads look where and which directions in the residual stream scratchpad have the most pull.

That’s why LLMs can be both amazing and frustrating with the same weights. The brilliance is what it looks like when state‑sensitive and anchor‑sensitive heads are doing useful work together. The brittleness is what it looks like when, for a moment, the less useful elements dominate the landscape.

Seeing that doesn’t magically fix anything. But it does change the question.

Instead of asking “does this model understand?”, or “why did it fail this time?” you can ask:

In this behaviour, which internal forces probably dominated (states, routes, or anchors) and how might that balance be shifting?

If you look at LLMs that way, the fragility isn’t just a quirk. It’s a clue to how the geometry is actually wired and to how we might, over time, shape it into something less brittle and more reliably brilliant.