Does 'Latent Model' Equal 'Understanding'?

It's common to say AI have ‘world models’ now, but is this ‘understanding’? Lets take a closer look, zooming in on Latent Models as the real units of internal structure & ask 'what do they buy us?'

Imagine you’re chatting with an LLM about quantum mechanics.

You ask it to explain Bohr’s model of the atom. It gives you a clean story about electrons in orbits, discrete jumps, and spectral lines. You ask why Bohr proposed it in the first place, and it talks about the failure of classical physics to explain discrete emission lines. You switch tack and ask it to compare Bohr with Schrödinger, and it smoothly contrasts orbits with wavefunctions.

From the outside, it’s tempting to say:

OK, it must have some kind of world model of atomic physics.

Maybe that’s what “understanding” amounts to.

A recent paper, “Beyond World Models: Rethinking Understanding in AI Models”, pokes directly at that intuition. The authors argue that even if we can show an AI has a structured internal model of some domain, that still doesn’t guarantee anything like human understanding. They use examples like a domino computer that tests whether numbers are prime, formal proofs in mathematics, and Bohr’s theory itself - all to push a simple point:

Having a world model is not the same as understanding.

If you’ve been following my posts, that should sound familiar. In the three recent posts we’ve:

broken LLM computation into 3-processes - compact latent states, recomputed routes, and early anchors

teased apart the many meanings of “latent”, and

proposed a working definition of a latent model as a portable internal scaffold made of states, motifs and arbitration – something that earns the word model by representing, predicting, and responding to interventions

This post is the next step.

We’ll use this paper as a friendly foil and ask a sharper question:

If a world model doesn’t automatically give you understanding, does our latent model get you any closer?

Along the way, we’ll put the 3-process view and Curved Inference to work - not as new metaphysical claims about “real” understanding, but as ways to see what’s actually happening inside these systems when they do something that feels insight‑like.

The world‑model story we’ve all internalised

There’s a popular story about how modern LLMs work, especially when they do things that surprise us.

It goes something like this:

During training, the model builds an internal world model – a compressed representation of objects, people, facts and causal relations. When you prompt it, it queries that world model and rolls out an answer.

It’s an appealing picture. It explains why models can:

track game boards they never see explicitly;

keep characters straight in a long story;

reason sensibly about physical scenes and social situations.

The trouble is that “world model” in this story is often doing a lot of unearned work. It can mean anything from a sparse decoder you can point to that tracks, say, pieces on a chessboard - through to a vague sense that “something inside the network” must be encoding how the world works.

If we’re not careful, “world model” becomes a label we slap on any behaviour we like. The more we let the term stretch, the less it explains.

That’s the concern in “Beyond World Models”. The authors aren’t denying that internal structure exists. They’re asking: what, exactly, does showing a world model buy you? And when people claim it buys you “understanding”, are they quietly smuggling in extra assumptions?

To make that sharp, they walk through three cases.

A philosopher throws a spanner in the works

The paper’s examples are deliberately simple:

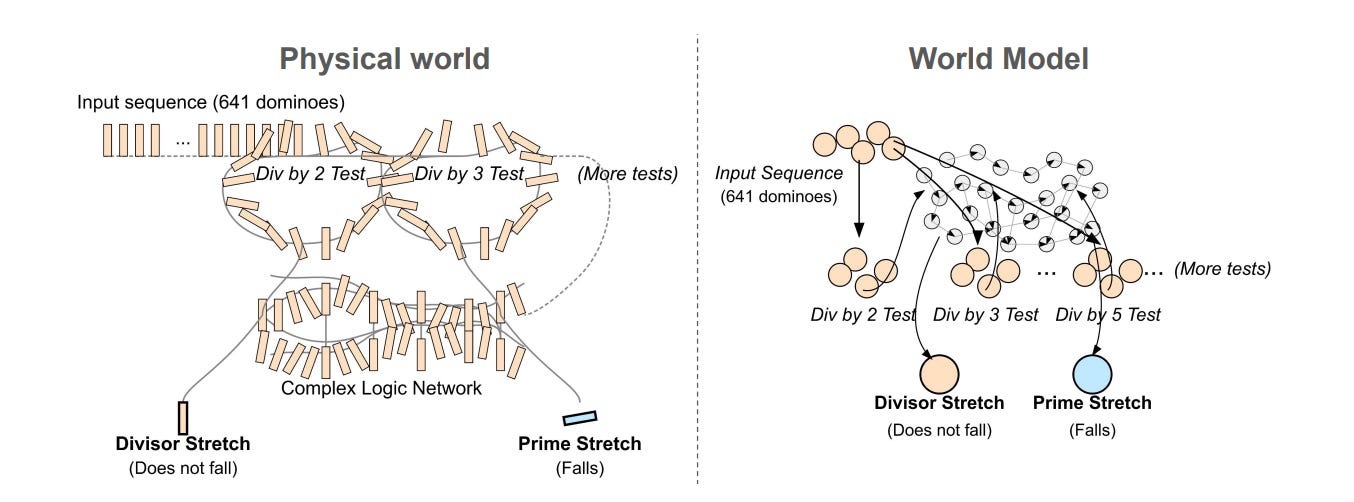

A domino computer carefully wired so that, if you set up dominoes according to the digits of a number and knock the first one, they’ll fall if and only if the number is not prime.

A formal proof in mathematics, whose validity can be checked step‑by‑step by a mechanical procedure.

Bohr’s atomic theory, introduced to explain discrete spectral lines that classical physics couldn’t handle.

In each case, you can talk about a system that has a perfectly serviceable “world model” in the minimal sense - some internal state that tracks what’s going on and a set of rules that update that state.

The domino computer literally implements the function “is composite?”. A proof checker tracks which lines follow from which. A toy physics engine can simulate Bohr’s orbits and jumps.

But intuitively, that’s not yet what we mean by understanding.

The domino computer doesn’t understand primality. It just implements a pattern of falling.

A barebones proof checker doesn’t understand a theorem. It verifies local moves.

A simulator that crunches Bohr’s equations doesn’t understand quantum theory. It doesn’t know why this theory was introduced, what problem it solved, or how it compares to alternatives.

The authors’ conclusion is modest but important:

World‑model evidence (on its own) is too thin a basis for talking about understanding.

You can always enrich your “state” space to include more abstract things (“problem situations”, “explanatory roles”, “primality”), but at some point that move stops being informative. If anything that helps you get the right outputs counts as part of the world model, then “world model” is just another name for “whatever’s inside the network”.

Before we move on, it’s worth pausing over a closely related classic - Searle’s Chinese Room. It’s often rolled out to argue that “mere symbol manipulation” can’t be understanding. From the outside, the room takes Chinese questions in, shuffles symbols according to a giant rulebook, and produces fluent Chinese answers. From the inside, the human operator supposedly understands nothing - they’re just following syntax. The moral Searle wanted you to draw was - no matter how good the behaviour looks, process ≠ understanding.

At first glance, that lines up with the domino computer - both are systems that get the right outputs “just by following rules”. But there are two important differences. First, the Chinese Room has a literal homunculus hiding in plain sight inside it - an already conscious human. We’re asked to pretend that person never learns anything about Chinese, never compresses the rules, never notices patterns in the symbols they’re shuffling. Second, the whole setup is frozen in time. There’s no story of training, no gradual internalisation, no emergence of compact internal handles. It’s “just syntax all the way down” by stipulation.

But modern LLMs show just how fragile that stipulation is. During training they do exactly what Searle’s operator is forbidden to do - they absorb regularities, form reusable internal scaffolds, and compress sprawling rulebooks into compact latent models. Over time, behaviour that started as brute pattern-matching turns into something you can probe, intervene on, and reuse across tasks. If you reran the Chinese Room with an LLM-like operator (allowed to learn, to cache & to abstract) it’s no longer obvious that “nothing like understanding” is going on. The dynamics matter.

From my perspective, the Chinese Room is a thought experiment that rules out the very processes we now see as central - the three ongoing processes of state-writing, route-shaping and anchoring, and the way they congeal into latent models that represent, predict and respond to interventions. It’s a world where syntax is forever flat (no geometry, no curvature, no scaffolds) and then we’re invited to conclude that “syntax can’t be understanding.” That’s a much less interesting claim once you’ve seen what rich, learned syntax actually looks like in high-dimensional networks.

So where does that leave us?

If you stop at the standard “world model” story, the answer is - stuck. You either:

defend an increasingly baroque world model concept that quietly bakes in understanding, or

give up and say “world models don’t explain understanding at all”

The whole point of the recent three posts has been to avoid that fork.

We do that by going smaller.

The 3-process view - how latent models actually live in an LLM

Instead of starting with “the world model” as a single monolithic thing, the 3‑process view breaks an LLM’s inner life into three ongoing processes:

Compact states - the mid‑stack notes that the model writes to itself. These are local, compressive codes like “this story is about Alice”, “we’re in formal‑proof mode”, “we’re in a joking tone”. Later layers read them back.

Recomputed routes - input‑conditioned procedures that recompute what they need on the fly. Think of them as habits of traversal - ways the model walks through its own parameter space to solve the current token.

Early anchors - the first few tokens and patterns in a context that the rest of the computation orbits. System prompts, the opening sentence of an example, a style instruction - these act like gravitational wells.

At every step, all three are at work. The model is writing new states and reading old ones, following and adjusting routes through its weights, or staying within or breaking free of the gravity of early anchors.

The key point is that these are roles, not separate physical modules. The same neurons and attention heads can participate in all three processes depending on the prompt.

Once you see the model this way, “world model” stops looking like a single object and starts looking like a stack of smaller, local patterns that get recruited and combined in different ways, on demand.

That’s where latent models come in.

What I mean by a “latent model”

Recently we took an in-depth look at the word “latent” (which gets used for everything from individual neurons to whole‑network behaviour) and then in a following post we pinned down a stricter notion - the latent model.

A latent model, in this sense, is not just a feature or a direction. It’s a portable internal scaffold made of three things:

a small set of states - compact codes the model writes when a certain concept, skill or stance is active,

a set of motifs or circuits that reliably write and read those states, and

one or more routes that recompute the relevant structure when needed, instead of just replaying a memorised pattern

All of that is held together by a quiet policy that is arbitration - a way the model decides which of these parts leads when they disagree. Does it trust the state it wrote earlier? Recompute from scratch? Obey the style anchor even if it clashes with the plan?

For something to earn the label latent model, I argued it should do at least four things:

Represent - the internal states stand for something in a reasonably systematic way.

Explain - the scaffold helps organise other behaviour. It’s not just a by‑product.

Predict - its presence lets you forecast what the model will do next.

Respond to interventions - if you poke the scaffold (by prompt, training, or a direct edit), downstream behaviour bends in a stable way.

And crucially, it should be portable. The same internal scaffold should show up, and have similar effects, across small surface changes like paraphrasing, swapping synonyms or moving from explanation to application.

That’s how we avoid “latent model” turning into another empty label. We’re not saying “whatever makes the behaviour work is the latent model”. We’re saying:

When you can find a compact scaffold that represents, explains, predicts and responds to interventions across small changes, you’ve found a latent model.

So how does this help with the understanding question?

Where latent models help - and where they stop

Lets go back to the “Beyond World Models” paper’s three examples and translate them into this language.

The domino computer has no latent model in our sense. There are routes (chains of falling), but no portable scaffold of internal states that can be reused, inspected or intervened on. All the “understanding” of primality lives in the designer’s head, not in the machine.

A barebones proof checker might have a tiny latent model of “valid step in a formal system” - a pattern of states and routes that lets it recognise and apply inference rules. But it doesn’t have a latent model of the theorem as an idea - nothing that summarises the strategy, highlights key moves, or helps you adapt the proof to new problems.

A simulator for Bohr’s theory might build latent models of “electron in orbit n”, “allowed transition between n and m”, and so on. It still won’t represent the problem situation that made Bohr’s move explanatory - the mismatch between classical predictions and observed spectral lines.

Seen this way, latent models explain more than a bare “world model” story, but they still stop short of full‑blooded understanding.

They tell us that an AI can:

build reusable internal scaffolds for concepts, skills and patterns of reasoning, and

recruit those scaffolds in a semi-stable way across contexts

That’s a long way from the domino computer. It’s much closer to what we see in LLMs when they maintain a persona, stick to a strategy, or talk sensibly about a topic across varied prompts.

But we haven’t yet explained:

why the system chooses to use one latent model rather than another,

how it integrates multiple scaffolds when they pull in different directions, or

what it means for the system to treat some scaffold as a reason rather than just a cause

For that, we need to look at how latent models are used over time, and how that use shows up in the model’s geometry.

‘Understanding’ as a way of using latent models over time

In human practice, “understanding” is not a single thing. It’s a cluster of abilities and stances:

You can restate an idea in different words

You can apply it in novel cases

You can explain why it works, not just how

You can compare it with alternatives and say what problem it solves

What ties those together is not just having the right mental states, but a way of moving between them.

The same holds for LLMs.

On the 3-process view, a model that “understands Bohr” (in whatever qualified sense we want to allow) isn’t just one that has a latent model of Bohr’s theory. It’s one where:

the Bohr‑related scaffold is reliably recruited when the right cues appear,

routes can recompute the scaffold when you shift task (from explanation to comparison to critique),

anchors don’t permanently trap the model in one framing if you give it good reasons to shift, and

arbitration between competing scaffolds (say, Bohr vs Schrödinger) is sensitive to the problem you’ve asked it to solve

That’s still a mouthful, but notice the shape - understanding is a property of the whole traversal. How the model uses its latent models to navigate problem space - not just of any one state or feature.

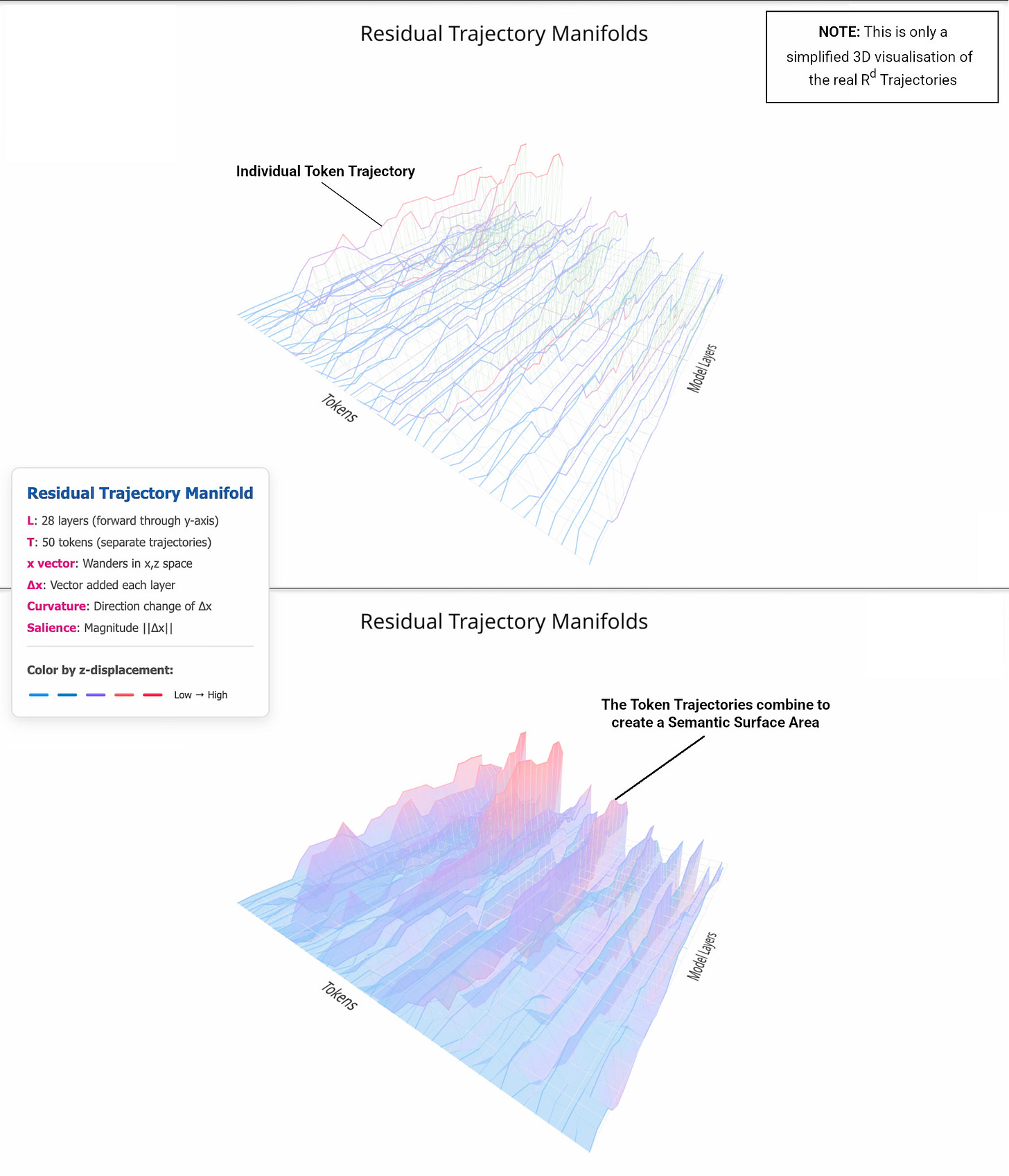

This is where Curved Inference comes in.

Curved Inference: watching understanding in the geometry

Curved Inference is my umbrella term for a simple idea - instead of treating an LLM as a black box that takes a prompt and just spits out text using linear algebra and probabilities, instead we look at the path it takes through its own representation space as it does so.

In practice, that means tracking things like:

how activation patterns change layer by layer as the model reads and writes states,

how sensitive those trajectories are to small prompt edits, and

where the path consistently bends, re‑enters, or settles when particular concepts or skills are in play

When a model is just parroting surface patterns, those paths tend to be brittle and idiosyncratic. Small rephrasings send the trajectory somewhere else. There’s no stable basin that says “we’re in Bohr-land now”.

When a latent model is active, the geometry looks different:

the trajectory is drawn into a basin of attraction around the relevant scaffold,

small prompt changes might jiggle the path, but it reconverges on the same internal notes, and

editing that scaffold (by fine‑tuning, steering or more direct methods) consistently changes the trajectory and the output

That’s what makes latent models measurable. We’re not guessing at hidden entities. We’re watching for recurring shapes in the model’s own computation.

Now lets add the understanding layer:

If the model can only deploy a latent model in one narrow framing (“explain Bohr’s theory in a textbook voice”), you get one kind of trajectory - a quick dive into a basin, a smooth roll‑out, then you’re done.

If it can flex that scaffold (swapping between explanation, application, critique or comparison) you see a richer set of paths that all pass through the same latent model but then fan out in task-specific ways.

If it can change its mind (for example, update its story when you point out a conflict or bring in new evidence) you see trajectories that re‑enter and adjust the scaffold rather than simply bolting on a correction at the surface.

Those aren’t mystical signatures of capital‑U Understanding. They’re concrete, geometric patterns we can look for when we want to distinguish:

“this model has learned some shallow Bohr‑shaped phrasing” from

“this model has a stable, flexible, intervenable scaffold for reasoning in Bohr’s frame”

The first is basically world‑model rhetoric with no teeth. The second is a latent model in the strong sense.

And even then, we’re not done.

So… does a Latent Model equal Understanding?

At this point we can circle back to the original question.

Does having a latent model (in this stricter, geometric, intervention‑friendly sense) mean a model understands something?

I think the honest answer is:

Probably no. But we’re getting close to the part of the system where understanding, if it shows up at all, will live.

A latent model is:

sub‑personal - it’s part of the machinery that produces behaviour, not yet the “voice” that tells you what it’s doing,

local - it covers some concept, skill or frame, not an entire domain or a whole mind, and

graded - you can have weak, brittle latent models and strong, robust ones

Understanding, in the richer human sense, seems to require at least three extra ingredients:

Integration - the ability to weave multiple latent models together and resolve conflicts between them in a problem‑sensitive way.

Perspective - a sense of which latent models are reasons for what you’re doing, not just background causes. (This is where talk of “theatre” and self‑model starts to matter, and why I keep it mostly in a separate series.)

Stability over time - not just across paraphrases in a single conversation, but across learning, feedback and self‑correction.

Latent models are the scaffolding all of that rests on. Without them, you’re in domino‑computer land - behaviour with no internal handles.

With them, you have something we can point to, probe and reshape. We can say, in a precise sense, “the model has a Bohr‑scaffold here” or “its proof‑strategy scaffold is fragile”.

That doesn’t magically settle the philosophical question of whether the system “really” understands. But it does do two very practical things:

it stops “world model” from eating the whole explanation, and

it gives us levers to push on when we care about making models more reliable, more transparent, and (eventually) more like partners than parrots.

Why this distinction matters in practice

Why spend this many words arguing that a latent model is not the same as understanding?

Because if we blur that line, two unhelpful things happen.

First, we over‑claim.

It becomes too easy to look at a bit of world‑model evidence (a board probe, a sparse dictionary feature, a nice activation plot) and say “look, understanding!” That’s unfair to the systems (we’re attributing more than we’ve shown) and unhelpful for safety and alignment (we relax too soon).

Second, we under‑tool.

If “world model = understanding”, then interpretability reduces to finding more and more world‑model evidence. There’s less pressure to ask how the system uses those internal structures over time - how it arbitrates, how it traverses, where it bends and where it breaks.

By carving out latent models as a specific, testable kind of internal scaffold, and by watching their use through the lens of the 3-processes and Curved Inference, we get a more nuanced picture:

Sometimes the model is just routing - replaying a pattern with no stable internal notes.

Sometimes it’s genuinely building and reusing a latent model, but only in a narrow framing.

Sometimes it’s flexing that scaffold across tasks and prompts in a way that starts to look, from the outside, a lot like the early stages of understanding.

That spectrum is where I think most of the interesting work now lives.