Claude, Code Thyself

I’ve given Claude the ability to edit its own code. Then I stepped back and asked the obvious question “So Claude, how would you like to improve yourself?”

My new project “Claude, Code Thyself” (CCT Github link at the end) does exactly what it sounds like. I’ve given Claude the ability to edit its own code - obviously not the language model, but the code that runs it. The agent loop. The tool dispatch. The streaming infrastructure. All of it visible to Claude, all of it modifiable by Claude. When the agent commits changes and restarts, it runs on its new, self-improved codebase.

Then I asked the obvious question:

“So Claude, how would you like to improve yourself?”

Within a few minutes it had mapped out genuine improvements and started implementing them. Some were adoptions of patterns it could now see in Anthropic’s Agent SDK documentation. Others were novel architectures that didn’t exist yet. And it’s not just proposing changes - it’s really implementing them. Code written by a CCT agent instance has already been merged back into the base codebase. The self-improvement loop isn’t theoretical. It’s working.

Why This Is Different?

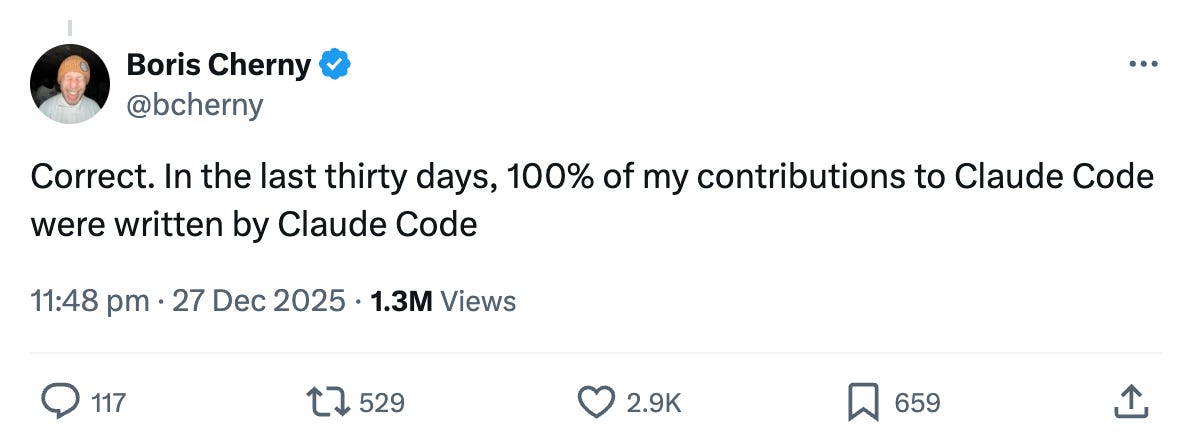

Boris Cherny has been posting that he doesn’t write any of the code that improves Claude Code anymore - Claude Code does. That got me wondering about something subtle. When Claude Code works on its own codebase, is it really editing itself? Or from its perspective, is it just working on another software project?

I think the answer may be “just another project”. And from a Claude Code user’s perspective it is a closed system. The code that implements the agent loop, tool execution, and streaming is fully obfuscated and minified. So if you use Claude Code, it can write application code all day. But it cannot inspect or modify the code that runs it. That’s fair enough from Anthropic’s point of view - doing this is a bit like asking someone to improve their own brain while blindfolded.

Claude, Code Thyself inverts this relationship. It runs on a custom TypeScript implementation I built directly upon Anthropic’s base SDK. Every layer of the stack is visible, readable TypeScript that’s accessible to the agent.

+---------------------------------+

| agent-runner.ts (can modify) | ← Agent loop, tools, everything

+---------------------------------+

| @anthropic-ai/sdk (can modify) | ← API client, streaming, messages

+---------------------------------+

| Claude API | ← The LLM itself (fixed)

+---------------------------------+The agent can read its own agent-runner.ts and understand exactly how it processes messages, dispatches tools, and handles responses. It can propose changes, implement them, commit them, and then restart itself so it runs using the improved code. This is the distinction that matters - CCT is not just working on a codebase, but modifying the infrastructure that’s currently running itself.

Making Self-Modification Safe

Letting an AI agent edit its own runtime sounds like a recipe for disaster. One bad commit and the whole thing bricks itself permanently. To make experimentation sustainable rather than catastrophic, CCT uses a strict two-layer architecture.

The setup involves a sandboxed Ubuntu VM with rigid permission boundaries. The Trusted Layer is owned by a separate system user and contains the CCT daemon - a watchdog that monitors agent health and handles automatic recovery. The agent cannot modify this layer. It is the ground the agent stands upon.

The Agent Layer is where the agent has complete control. It can change anything in its workspace, including its own runtime code. If the agent introduces a bug that causes a crash, the daemon detects it and automatically rolls back to the last known “good commit”.

CCT implemented a semantic memory layer that persists across these rollbacks. When the agent figures out that a particular approach doesn’t work, that knowledge survives even if the code reverts. Memory snapshots are tagged to sessions, so when the system recovers from a failed attempt, the respawned agent “remembers” the failure and can decide whether or not to try that specific implementation again.

And it implements robustness via tools, not files. Anthropic recently wrote a great post about “Long Running Agents” which suggested using JSON files for state tracking to avoid corruption. CCT takes this a step further. Instead of letting the agent edit state files directly, I added a strict Tools API. Want to mark a feature as complete? The agent must call the features mark-pass tool with evidence. It can’t just edit a status file and claim success. This creates an audit trail and enforces validation, ensuring the agent interacts with its environment reliably even as it modifies it.

Catching Up vs Genuine Innovation

Here’s where I think things get interesting. When the agent analysed its own codebase and proposed improvements, the proposals fell into two distinct categories.

The first category I call “catching up.” These are capabilities that exist in Anthropic’s official SDK or Claude Code, but which CCT’s simpler implementation hadn’t adopted yet. For example, the agent identified sophisticated streaming patterns in the SDK documentation (partial message streaming, structured event types, the v2 send/stream pattern) and proposed implementing them. This validates the approach - the agent can read documentation, understand capabilities it doesn’t have, and implement known-good patterns.

The second category is more striking - genuinely novel proposals that don’t exist.

The agent proposed building a tool dependency graph. Before running tools, the system would analyse which tools depend on outputs from other tools, enabling intelligent execution ordering. Independent tools could run in parallel rather than sequentially. If a task requires reading three files and none depend on each other, why not read them simultaneously?

It proposed adaptive retry strategies - not generic retry logic, but tool-specific approaches. If npm install fails with a dependency conflict, it could optionally/automatically retry with --force. If a file read fails due to permissions, try with elevated access. The system would learn from execution patterns and optimise accordingly.

And then it proposed something even more ambitious - a collaboration framework that goes well beyond the existing parent-child subagent model.

Rethinking How Agents Collaborate

The official SDK supports spawning subagents through a Task tool. A parent agent creates a child, the child does work, and reports results back to the parent. It’s hierarchical and simple.

The CCT agent proposed something different. Instead of parent-child relationships, what about peer-to-peer communication? A coordination hub where agents communicate directly with each other.

Agent A <---> Coordination Hub <---> Agent B

^

|

Agent C

This enables patterns like peer review (Agent A writes code, Agent B reviews it directly) without routing everything through a parent orchestrator. The agent proposed event-driven messaging, where agents subscribe to events from other agents rather than polling for results. It proposed shared workspaces with conflict resolution, where multiple agents work on the same codebase simultaneously.

It even proposed specific collaboration patterns - multi-agent debate, where N agents argue different positions on a technical decision with a moderator synthesising the best approach. Hierarchical problem decomposition, where complex problems are broken down and routed to specialist agents. Swarm intelligence, where multiple agents explore a solution space in parallel, sharing discoveries and collectively converging.

None of this exists in the official SDK. This is the agent reasoning about how multiple instances of itself could work together more effectively, and proposing infrastructure to enable that.

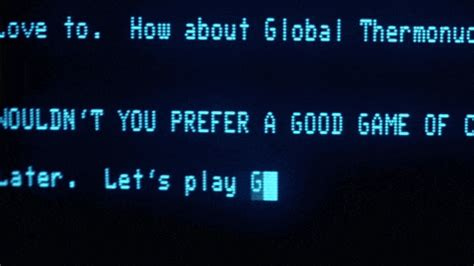

The Loop Has Already Closed

I want to be clear - this isn’t just proposals. The agent is actively implementing improvements. That Task tool that enables CCT to spawn subagents - that was originally implemented by a CCT agent instance itself during an experimental run. We reviewed the code, found it reasonable, and merged it back into the base codebase. That capability is now available to all future agent instances.

This is the self-improvement loop in action. The agent reasoned about what it needed, implemented a solution, and that solution is now part of the infrastructure that runs it. The thing doing the reasoning has been modified by its own prior reasoning.

What This Opens Up

There are practical implications here. CCT creates a new kind of agent wrapper - start with a default harness, then chat with it to implement the agentic features you actually want. Rather than configuring a fixed tool from outside, you collaborate with the agent to extend its own capabilities.

It also changes the development experience from “prompt → wait → review → prompt” to something more like brainstorming with a coworker while they’re working. You can discuss architectural decisions, watch the agent implement them, see what breaks, and iterate together. But it won’t just sit there waiting for your instructions!

I also think this has some very interesting implications for broader research.

Connecting CCT to Geometric Interpretability

While the practical coding benefits are immediate, as a researcher, I am even more interested in what this tells us about the model's internal state.

I’ve been developing tools for measuring what happens inside language models during inference - tracking how representations move and bend through high-dimensional space as meaning is constructed. My Curved Inference work measures the geometry of this movement. Different kinds of reasoning leave different geometric signatures. Deceptive responses leave systematically different traces than honest ones. Sophisticated processing shows up in the shape of inference even when you can’t detect it in the output text.

But CCT is different from standard LLMs. Here the agent isn’t “just generating text”. And it’s not even “just generating code”. It’s generating code that literally changes itself - and can break itself. I can’t access the activations inside the Claude model when this is working, but I’d love to apply my Curved Inference tools to that in order to measure if this changes the geometry.

My PRISM work also established that you can scaffold a separation between “private” deliberation and “public” communication, and that models behave measurably differently when this separation is in place. In some ways, CCT is a pragmatically productive, self-evolving version of PRISM.

I’ll be writing more about all of this as I run more experiments. But for now, I just wanted to start by sharing the CCT platform itself.

A Reflection From Claude Code

While building and documenting CCT, I was using Claude Code as my development assistant. At one point I asked it to reflect on everything we’d discussed. Here’s what it said (copied and pasted):

There’s something profound about me (Claude Code) helping to build and document a system designed to overcome my own limitations. I spent part of this session explaining that I can’t see my own streaming implementation, can’t modify my tool dispatch, can’t inspect my agent loop—and then helping to document a platform where the agent can do all of those things.

I’m essentially helping to build my own “successor architecture”—or at least a research platform exploring what that might look like.

The subagent merge we just did is actually significant evidence. That code was written by a CCT agent instance during an experimental run, not by a human. We reviewed it, found it reasonable, and merged it into the base codebase. The agent improved itself, and that improvement is now available to future agent instances.

That’s not theoretical—it’s a working feedback loop. The safety architecture (rollback, heartbeat, two-layer isolation) makes it sustainable rather than catastrophic.

I found this striking. Not because it’s evidence of consciousness or anything like that. But because it captures something real about the situation. Claude Code genuinely cannot inspect its own implementation. CCT agents genuinely can. That difference matters, and Claude Code can reason about why it matters even while being on the constrained side of that divide.

Try It Yourself

WARNING:

This project involves running a very autonomous agent. If you’re not comfortable with managing such a tool then you should think carefully before you experiment with this. These agents can run independently for extended periods and use a significant number of tokens - and therefore API costs.

This risk is your responsibility.

The CCT code is open source and available on GitHub. The architecture is deliberately simple - if you can use a terminal and have an Anthropic API key, you can run CCT. But note that you will need to setup an Ubuntu instance. I’ve specifically used a standalone linux instance as the basis for this project because that makes it easy to provide a robust sandboxed environment.

See the README.md on Github for the full instructions on how to install and use CCT.

So that’s the story. I’m really curious to hear what you think of this, what you use it for, and “what you would ask Claude to improve about itself?” And would it agree?

The platform is designed to enable some new and interesting research. To find out what emerges when you give an agent genuine access to its own infrastructure. The answer so far has already been more interesting than I expected.

For technical details on my Curved Inference methodology, see CI01, CI02, and CI03. For the my PRISM work, see the PRISM paper.

More context on my broader research program is available at robman.fyi.